Photo Credit: Divine Effiong | Unsplash

In my last full-time position, I worked and lived in North Kivu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (“DRC”), arguably, the epicenter of what has become known as the “rape capital” of the world where the systematic rape of women is often used as a tool of war but rooted in the hegemonic patriarchy that defines the cultural context.

In such a context, women are portrayed truthfully but perennially as victims. The network that seeks to support these women through advocacy and policy proposals on human rights, health, education and livelihood intervention often struggles to strike the right balance between highlighting their victimhood and doing so in a way that doesn’t inculcate a debilitating victim pathology.

The imperative is to provide support that brings constructive attention to acts of victimization committed against women at the same time that we help them to connect to their own considerable power.

African women, in particular, walk a fine line between asserting their power in escaping victimhood and risking alienating male partners and allies in many African countries where the contestation for power between disparate groups is often seen as a zero sum game.

To put it simply, the ascendency of women is often perceived as an outright loss for men. In a seminal report of a gender assessment conducted by USAID in DRC, the researchers reported that this was a popularly held misconception among many Congolese. According to the report,

“Programs targeted specifically at women’s empowerment were said by some informants to be (mis)understood as an attack upon men . . . .Fewer women were elected to the National Assembly in late 2011 than in the previous election, suggesting that there may be a backlash underway.” The Final DRC Gender Assessment, Aug 23, 2012

The idea of “zero sum” playing out in the context of the power relationship between men and women in Africa, is sometimes reinforced in film through a well-meaning intent to inspire women to transform victimhood into power.

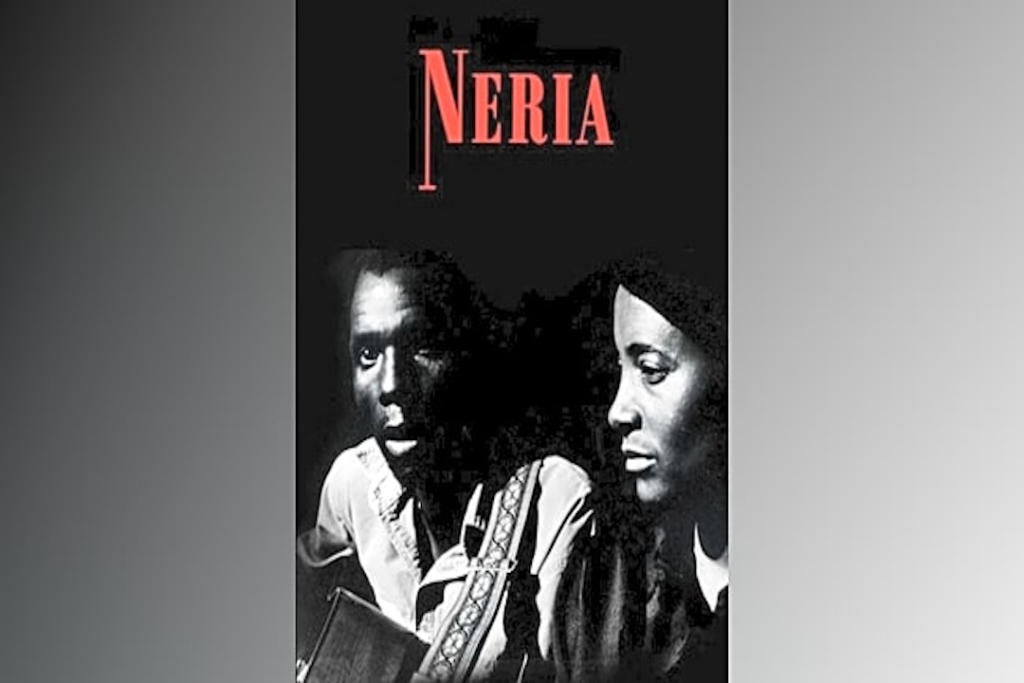

In the 1991 film set in Zimbabwe, NERIA, a woman who is victimized by the common practice of widow divestment, an oft overlooked aspect of women’s victimization, the title character, Neria loses her devoted husband to a cycling accident at the beginning of the film.

The injury of this tragic loss is further compounded by her husband’s male relatives’ efforts to divest her of all possessions according to a distorted version of the traditional notion that the dead husband’s family is obliged to care for the widow.

In the film, she is helped to assert her rights to the recovery of her possessions and the male relatives are defeated. It is a beautiful film that can be seen at this link.

This is a wonderful “feel-good” story that I have often used to inspire women in the various countries where I have worked. But how can we use film and multimedia to also demonstrate how much the empowerment of women can redound to the benefit of whole societies?

In a dialogue I hosted featuring the former president of Malawi, Joyce Banda, she makes a distinction between Western feminism and African feminism where African women pursuing a feminist agenda in a stubbornly patriarchal context are obliged to employ guile and subtlety so as not to pose an overt and alienating threat to men.

Given the dominance of men in Africa, cultivating male “ally-ship” becomes an imperative – a process on the Continent where efforts are progressing but extremely incrementally.

Dr Banda’s own story and that of other leading African women like Wangari Maathai, portray the bleakness of how often women who aim to assert their power pay the price of a failed marriage.

Unlike Maathai, Banda, who escaped from her abusive first marriage as she was connecting to her power potential, found a model male ally in her second husband. Judge Richard Banda was instrumental in his wife’s bid to claim the presidency when dark forces sought to deny her constitutionally mandated right to be elevated from her position as VP after the death of the president.

Maathai’s husband filed for divorce on the basis that his wife was too “strong minded for a woman” and could not be “controlled.” In contrast, far from blocking his wife’s leadership aspirations, Richard Banda has continuously encouraged her at each step of her rise to the top of Malawian politics.

The two men represent the polar ends of Africa’s vast spectrum of expressions of masculinity. The positive masculinity that Judge Banda represents is an aspirational aspect of African feminism.

What underpins positive masculinity and leadership, in general, is a belief in what the current development literature espouses based on irrefutable evidence – that the empowerment of women and an inclusion ethos that creates opportunities for all historically marginalized groups, including minorities and LGBTQ communities, are drivers of growth and development.

So what should a feminist agenda look like in the African context where the need for social and economic development is as compelling as the need for gender equity and inclusion?

- ENGAGE INFLUENTIAL SPACES

- A long term effort to transform cultural norms that militate against an inclusive ethos chiefly through the development of a substantial body of feminist educational material and curricula at primary and secondary school level that will systematically inculcate positive masculinity among boys and young men, empowered femininity among girls and young women and a greater sense of support among those struggling with sexual identity at an early age. See my book of comprehension readers on African women for middle school learners available on Amazon at this link.

- Engage traditional and religious leaders in non-threatening ways, invoking feminist theology and the feminism represented in oral African traditions – enlist them as allies for promoting feminist theology and traditional culture.

- Open political spaces for the historically marginalized through creating more platforms that help them develop as inclusive leaders and viable candidates.

- Establish platforms that link the grassroots to regional bodies to ensure local input into national and regional policy dialogues on equity and inclusion.

- Engage media in Africa to promote images and models of positive masculinity and empowered femininity (making connections between the empowerment of women and the positive impact it has on development), the power of feminine energy and increased normalization of alternative sexual identities.

- PROMOTE CONCEPTS

- Emphasize and heighten the profile of the “care-centricity” of feminine energy to make it safe for women and men to channel and apply such energy when they find themselves in leadership positions in whatever sector.

- CREATE AND SUSTAIN NETWORKS

- Link feminist and inclusion platforms within Africa and between Africa and its Diaspora and between Africa and the rest of the world to build mutual support for feminist and inclusive causes.

Already many feminists on the African continent are employing some of these and other strategies tailored to the context. But when taken together, they begin to form a roadmap for effecting lasting transformation in favor of achieving a vision for Africa in the latter half of the 21st century that is “inclusion-centric.”